Your unique mode of knowing: How it shapes the way you learn, create, and thrive

By embracing the unique ways we’re wired to know—through movement, sound, or sight—we transform how we learn, create, and experience the world.]

When I was in college, I took an astronomy class (twice) and failed it both times. After the wonderful lectures in the planetarium where we gazed at the constellations above, I would walk out of the room and not remember a thing. I couldn’t believe it—failing classes wasn’t something I did. So, I took the class again, but I failed once more. It wasn’t until I read Dawna Markova’s research that I understood why: my learning style didn’t align with the teaching method.

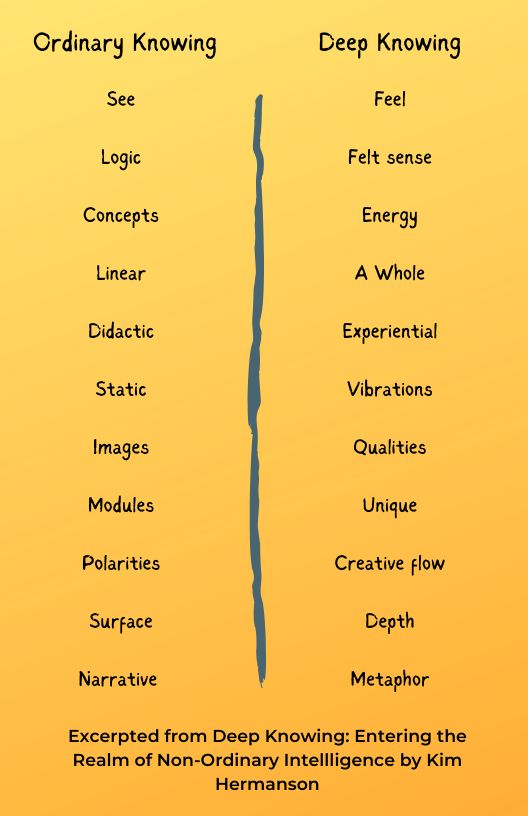

The concept that there are 3 modes of knowing [kinesthetic, auditory, and visual] is not new.

- Kinesthetic knowing is rooted in physical movement and bodily sensations. People who engage through this mode often need to move to think, learn, and gain deeper insights.

- Auditory knowing involves processing information through sound, such as listening to speech, music, or environmental sounds.

- Visual knowing is centered on images, symbols, and the visual realm. People with a visual mode of knowing often process information through images or diagrams.

It’s also not new that each of us favors one of those 3 modes. But Markova took her research a step further by explaining that each of us have all 3 ways of knowing, but we’re hooked up differently to them. Knowing how you process these different modes is important because it will tell you not only how you learn best (direct classroom learning requires being fully conscious, while for intuitive guidance or creative work we’re drawing on ‘subconscious’ processes).

For example, some of us are stimulated by kinesthetic knowing, while for others, kinesthetic knowing makes them drowsy. Same is true for auditory or visual knowing. Some people easily imagine images with their inner eye (visual knowing), while others don’t have that capacity at all.

There is no right or wrong way to be hooked up to these learning channels.

Reflecting on my own experiences, I see how my primary mode of knowing—kinesthetic—has shaped my learning and creativity. In college, I could easily fall asleep during lectures. To stay engaged, I began taking notes on everything the professor said. This physical act of writing helped me stay alert and allowed the material to stick in my mind. Without that kinesthetic engagement, I found it was difficult for me to retain information.

The astronomy class I took is another perfect example. I loved the subject and was eager to learn the constellations, but I couldn’t retain the material. Despite attending the class twice, I failed both times. Why? The class was taught in a planetarium, where the instructor would point to the constellations in a dark room. Without a way to physically interact with the material (i.e., to write things down), I couldn’t connect to it in a way that would help me remember. As Markova’s research suggests, when I engage with my conscious mind through kinesthetic activities, the material becomes memorable. Without that ability, I struggled.

Markova’s research also highlights how auditory input can impact our state of being. For me, auditory input often has a calming, almost sleep-inducing effect, which means I struggle to stay mentally alert when the input is primarily auditory. This is why I often take notes or need to be physically engaged when learning or processing information.

But other people process auditory input differently.

When I taught creativity classes at Holy Names University, I played quiet background music during art projects. While I enjoyed the soothing sounds, some students had real difficulties with any kind of music, no matter how soft or calming. Those individuals likely had a strong auditory mode of knowing, and the music disrupted their deep creative flow. For them, the auditory input pulled them into a more conscious, alert state, which probably blocked their ability to access the more subtle, subconscious insights they needed for their creative work. (Those students would have done well learning in my Astronomy class.)

Next time you feel disconnected or struggle to retain information, take a moment to reflect: How are you wired to stay alert so that you can know at your best? And what is the part of you that can access more intuitive, under-the-surface inner guidance? For me, that way is visual (inner imagery) but for you it may be auditory or kinesthetic.

By embracing your individual ways of learning and engaging with the world, you can unlock deeper insights and ignite your creative process.

Check out Markova’s book, No Enemies Within