Inviting the Third Space: Teaching as a creative collaboration

One of the most captivating aspects of teaching—or any situation where people gather for an intentional purpose—is what I call Third Space. This is the mysterious and profound “in-between” that arises when people connect around something they care about.

Philosopher Hannah Arendt called it “an in-between.” Theologians describe it as a “Divine Third,” and Martin Buber referred to it as “Thou.”

When we form a genuine relationship with something we care about, it is no longer an “It.” Instead, it becomes something “Other,” imbued with depth and mystery. In this space, we don’t have all the answers, and we can’t plan or control the process. All we can do is put forth what we have, see what comes back, and adapt. This approach applies not just to teaching but to any meaningful relationship.

Honoring Third Space

To honor the wisdom of Third Space, we need to focus on creating space. This is counterintuitive because most of us are conditioned to fill space—with agendas, content, and information. But when we focus on creating and holding space, the deeper wisdom of Third Space emerges naturally.

Here are three simple yet powerful ways to invite Third Space into your teaching or group work:

1. Inspire Yourself First

Teaching is a creative process, and to access Third Space, you need to stay inspired. Spend time in places that make your heart open—a mountain, the ocean, or any expansive vista. Let the feeling of expansiveness nourish you. This inspiration fuels your ability to inspire others.

2. Focus on What Your Group Has to Say

The people in your group have questions, insights, and perspectives that matter. Facilitate their process, rather than prioritizing your own ideas or content. If you have essential information, provide it as a handout. To reach Third Space, you must drop your ego, expectations, and preconceptions. Teach from a place of emptiness—what philosopher Douglas Harding called “being headless.”

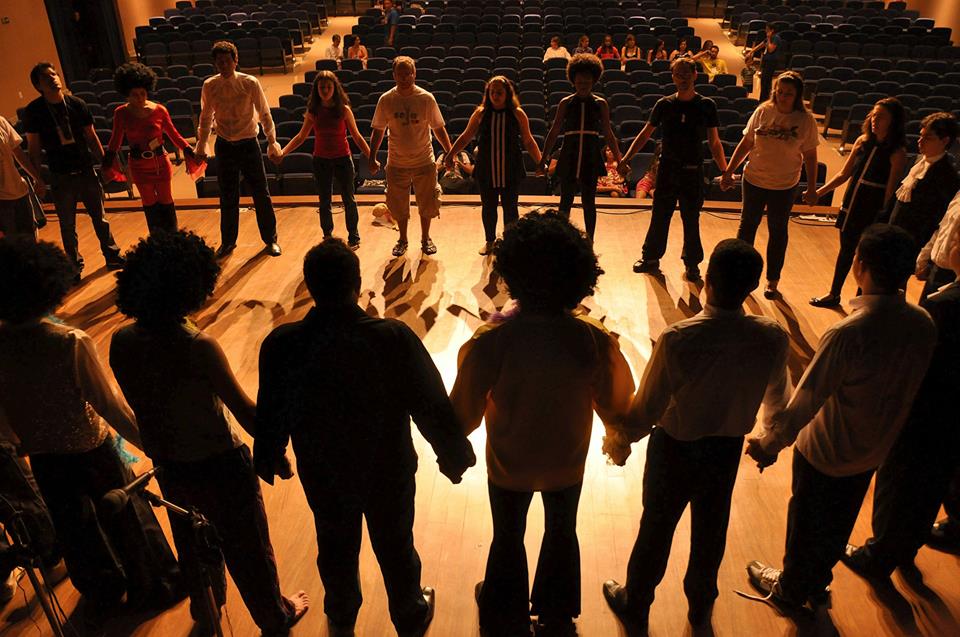

3. Create Structures for Equal Sharing

Use a clear structure to ensure everyone has space to contribute. Quiet or shy participants often have insights that can shift the entire group in profound ways. Avoid letting dominant voices monopolize the conversation. As Alan Briskin describes in The Power of Collective Wisdom, even a timid voice can bring forward the breakthrough idea the group has been waiting for.

The Paradox of Teaching

Teaching is not about leading or filling heads with knowledge. It’s about creating space for collective wisdom to emerge. As John Heider wrote in The Tao of Leadership:

“…their leadership did not rest on technique or theatrics, but on silence and their ability to pay attention… They were courteous and quiet, like guests.”

To reach Third Space, we must remember that we are guests in this shared experience. What an honor that is.

For more insights, read Chapter 6 of Getting Messy.